The Frescobaldi Thematic Catalogue Online

About the FTCO Project

The FTCO provides free public access to a thematic catalogue and database of all the known works of Girolamo Frescobaldi (1583-1643), including works of uncertain or mistaken attribution, along with all their early sources (up to approximately 1800), principal modern editions, and associated literature. It is a work-in-progress and may remain so for some time to come. We hope that with ongoing contributions and comments from the international musical and scholarly community, we will continue to improve the comprehensiveness, accuracy, and usefulness of the database.

The idea of compiling a thematic catalogue of the works of a composer is not a recent one. Johann Kaspar Kerll (1623-1695)––who at one time, mistakenly, was believed to have studied with Frescobaldi––appended the first few measures of each of his keyboard works to his Modulatio organica super Magnificat, published in 1686.

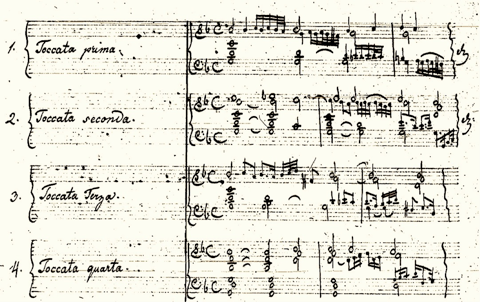

He hoped in this manner to establish his authorship for compositions that he had seen erroneously attributed to other composers. His concern appears justified: four toccatas whose beginnings are reproduced in the FTCO, survive in a manuscript in Bologna under Frescobaldi’s name (see F 18.01S to F 18.04S)!

The earliest thematic catalogue of the works of Frescobaldi was compiled by the noted Austrian musician-scholar-collector Aloys Fuchs in 1838, and survives as an unpublished manuscript in the Deutsche Staatsbibliothek (see Berlin K556). Fuchs’s catalogue only includes the works from five of Frescobaldi’s Canonical Keyboard Publications (see Definitions): the two volumes of Toccate, the Capricci, the Recercari, and the Fiori musicali. These comprise only about a third of the compositions listed in the FTCO, although they undoubtedly represent the best-known––and some might also argue, the best––of his works.

Like Kerll, and like the FTCO for that matter, Fuchs does not merely present the opening themes (i.e., melodies), but provides the beginning measures in full score. (When the source is printed in four-part open score or partitura, he provides only the soprano and bass lines.) “Thematic catalogue” is in fact a misnomer for these catalogues. The concept of “theme,” so central to our understanding of the music of the later eighteenth century and beyond, is not really appropriate to Frescobaldi’s time. Many of his toccatas and partite do not open with distinctive themes, and require a full-voiced setting to establish their identity––and that is what is provided in the FTCO.

No other thematic catalogue of Frescobaldi’s work has appeared until now, although during the course of the twentieth century there was a growing awareness of the extent of his œuvre beyond the canonical keyboard publications, in particular, his vocal and instrumental ensemble works and––beginning in the 1960s thanks largely to the efforts of WiIli Apel––the large manuscript repertory. The continuing absence of a complete thematic catalogue at a time when such catalogues had become available for most western composers of some note––for the famous as well as the less famous––may be due to the uncertainty and controversy that surrounds many of the works to which Frescobaldi’s name has been attached. The FTCO includes all those works, no matter how grave the doubts concerning their authenticity (or how certain the knowledge of their misattribution), but we do stigmatize the questioned or questionable works by noting their status as “doubtful,” “disputed,” “spurious,” etc. (see also F numbers). It may well be that as the result of new research, we will be able to remove that stigma from some works, or, for that matter need to attach it to others. The ease with which we will be able to make such and other revisions is just one of the many advantages of presenting this catalogue in electronic form, along with the ease of doing complex, multi-parameter searches and its easy world-wide accessibility.

How to cite the FTCO

Citations of JSCM Instrumenta should be in the same style as for printed books in a series. Citations of specific information should include the section name and whatever numerical or other location identifier is used in that section, followed by the URL. Since instrumenta are revised when new information becomes available, the date of revision is important in a citation.

We offer the following as a model:

Alexander Silbiger, Frescobaldi Thematic Catalogue Online, JSCM Instrumenta 6 (created 1 September 2010, new ed. 1 November 2021, last revised 1 November 2021), “About the FTCO Project,” par. 1, https://frescobaldi.sscm-jscm.org/the-ftco/about-the-ftco-project/.

About the General Editor and Project Director

Alexander Silbiger is Professor Emeritus and Former Music Department Chair at Duke University, Former President of the Society for Seventeenth-Century Music, and Founding Editor of the Web Library of Seventeenth-Century Music. His many publications include Italian Manuscript Sources of Seventeenth-Century Keyboard Music (1980); “The Roman Frescobaldi Tradition: 1640-1670,” in JAMS 33 (1980); “From Madrigal to Toccata: Frescobaldi and the Seconda Prattica,” in Critica Musica (1996); articles “Chaconne,” “Passacaglia,” and (with Frederick Hammond) “Frescobaldi,” in The New Grove (2001); “On Frescobaldi’s Recreation of the Ciaccona and the Passacaglia,” in The Keyboard in Baroque Europe (2003); “Fantasy and Craft: The Solo Instrumentalist,” in The Cambridge History of Seventeenth-Century Music (2005); and “Four Centuries of Frescobaldi Reception: How His Music Made Its Way through the World from His Time to Ours,” in A Fresco: Mélanges offerts au Professeur Etienne Darbellay (2013). He served as Editor of Frescobaldi Studies (1987) and of Seventeenth-Century Keyboard Music: Sources Central to the Keyboard Art of the Baroque (28 vols., 1987-89).